What is meningoencephalitis of unknown aetiology (MUA) or cause?

MUA is a group of autoimmune conditions where the body’s immune system attacks the nervous system for an unknown reason.

Inflammation of the brain and its lining is called ‘meningoencephalitis’. MUA is a term for a group of inflammatory brain conditions that can affect dogs of any age, sex and breed; although small breed, female, young to middle-aged dogs are more typically affected.

How can I tell if my dog has MUA?

The clinical signs of MUA are highly variable, reflecting the fact that MUA can involve any part of the central nervous system. Most commonly, MUA involves the brain, to cause your pet to exhibit any or all of the following:

- Fits (epileptic seizures)

- Blindness

- Disorientation

- Wobbliness and loss of balance

- Weakness

- Change of personality and behaviour

- Weakness of the jaw and/or difficulty swallowing

The signs can be sudden and severe in onset, or slow and insidious in their progression.

What is the cause of MUA?

MUA are a group of ‘immune-mediated’ or ‘auto-immune’ conditions; this means it is caused by the body’s own immune system. There are many different types of immune-mediated conditions in animals. Normally, the immune system targets a protein it comes into contact with in the environment (in something it touches, eats or breathes in; or something it gets minor infections from with bacteria/viruses/parasites) that matches a protein in the body, causing an inflammatory reaction.

We are not normally able to establish why an animal develops an immune-mediated brain disease. So, a genetic risk factor may play a role. However, animals of any age, sex and breed can be affected. Therefore, a complex interaction of genetics and the animal’s environment probably contributes to developing the condition.

Some specific types of inflammatory brain disease have been described from tissue samples, on the basis of the distribution of inflammation and the types of inflammatory cell involved – these include granulomatous meningoencephalitis (GME), necrotising meningoencephalitis (NME), eosiniophilic encephalitis (EE) and necrotising leukoencephalitis (NLE) – ultimately definitive diagnosis can only be made with brain tissue under a microscope, via a biopsy. Obviously, a biopsy of the brain is a very invasive and potentially risky procedure, so we do not normally recommend this in dogs – hence the normal descriptive diagnosis of meningoencephalitis of unknown aetiology (MUA).

How is MUA diagnosed?

As previously mentioned, a biopsy of the brain is a very invasive and potentially risky procedure, so we do not normally recommend this in dogs or cats. MUA is a clinical diagnosis. Several diagnostic tests can be performed to build a portfolio of evidence to support the diagnosis.

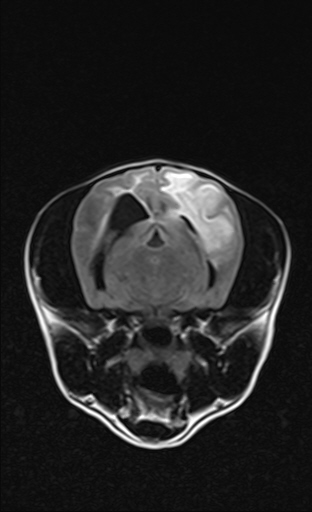

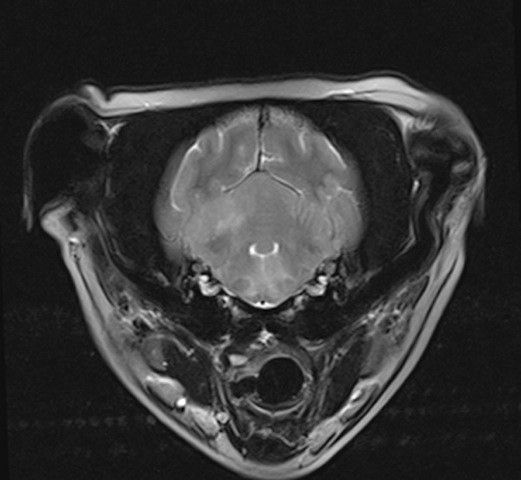

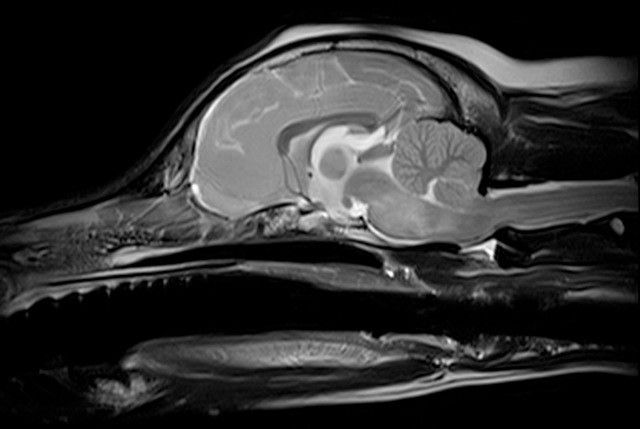

Very often your neurology clinician will recommend imaging the part of the nervous system affected, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Typically with inflammatory brain disease, the MRI shows abnormal patches of ill-defined increased fluid/cellularity. Rarely the MRI can be normal. Subsequently, cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) analysis helps aid diagnosis. CSF is produced in the brain to nourish itself and remove waste; with MUA we expect inflammation to spill into this fluid to be detected under a microscope. Again, we may be unlucky and the CSF rarely can be normal. So, using both MRI and CSF analysis combined increases the likelihood of a presumptive diagnosis. We may then advise ruling out common causes of CNS infections.

As the changes seen on MRI and CSF can be relatively non-specific (certain types of cancer that spread throughout the body can look the same) your neurology clinician may recommend ruling out cancer elsewhere in the body (particularly in the spleen and liver) as these organs are more readily amenable to biopsy.

If the MRI, CSF analysis and ancillary testing (blood tests, abdominal imaging) supports inflammation with no other concerns, a diagnosis of MUA can be made.

How is MUA treated?

The mainstay of treating your pet with MUA is suppression of his / her immune system with drugs, particularly high doses of corticosteroids like prednisolone. The administration of high doses of steroids by injection or orally very often results in significant improvement or resolution of the clinical signs. The dose is then reduced slowly over the course of several months, or until the stimulus for the immune system has waned.

Unfortunately, side effects are often seen with steroid use. Common dose-dependent side effects of steroids include increased thirst and hunger (consequently urination and weight gain), lethargy, panting, and increased risk of infections (respiratory, urinary etc).

Occasionally, additional medications are required, either to aid suppression of the immune system or to allow us to reduce the steroid dose without fear of relapse. Most of these second-line drugs are technically ‘chemotherapy’ drugs – but it should be noted that we use them at relatively low and safe levels and side effects are rare. We commonly use a biohazardous drug called cytosine arabinoside (cytarabine) given as an injection. Administration of this medication is via an intravenous infusion over eight hours in a very controlled environment and following strict health and safety protocols. Unfortunately, your pet excretes the hazardous material in the urine and faeces and to control the exposure to you, the environment, and other animals or people it is necessary for us to hospitalise your pet for two days while the treatment is carried out. A series of treatments are required every few weeks for a number of months until the condition is under control.

Be rest assured that with your pet’s regular visits, they’ll soon be a familiar face with our patient care team, and they’ll make your family member feel that a stay at the hospital is home from home! Other medications like cyclosporine and azathioprine can be used orally and can be administered at home by you.

Your neurology clinician or primary care vet will discuss with you the expected side effects of each of these medications.

What is the prognosis of MUA?

The prognosis for MUA is highly variable. Normally, a good initial response to treatment indicates a good prognosis. It is possible for animals to enter full or partial remission from the disease and maintain a normal or very good quality of life for many months or years.

Sometimes, treatment can be withdrawn with time, but more often, treatment will need to be continued at low doses for a long time and possibly for life – there is no way of knowing which scenario will be the case for an individual patient at the onset of treatment. Sadly, it is also possible that the response to treatment is poor.

Occasional visits to your own primary care vet may be required during the course of treatment. Your vet may suggest blood tests every few months to assess the function of your pet’s organs that may be affected by treatment. How often this is required will be dependent on your pet’s response to treatment.