What is the cranial cruciate ligament?

The cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) in dogs is the same as the “anterior” cruciate ligament (ACL) in humans. It is a band of tough but slightly elastic tissue that runs between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone), preventing the tibia from sliding forward and stabilises the knee, preventing it from over-stretching and excessive rotation.

Trauma to the ACL in humans is common and damage most frequently occurs during sporting activity like football, rugby and golf. The nature of CrCl disease in dogs is very different. Rather than the ligament suddenly breaking due to excessive trauma, it degenerates slowly over time, like a fraying rope. This important difference is the primary reason why the treatment options recommended for cruciate ligament injury in dogs are so different from the treatment options recommended for humans.

What is the cause of cruciate ligament injury in dogs?

Sometimes, the CrCL can rupture acutely (suddenly break), which can be a result of excessive loading of the limb, overextension and/or rotation of the tibia, which results in an overload of the CrCL. In the vast majority of dogs, however, the CrCL ruptures as a result of long-term degeneration, whereby the fibres within the ligament weaken and fray over time, losing their structure and function.

We do not know the precise cause of this, but genetic factors are likely very important, with certain breeds being predisposed including Labradors, Rottweilers, Boxers, West Highland White Terriers and Newfoundlands. Supporting evidence for a genetic cause was obtained by assessment of family lines, coupled with the knowledge that many animals will have a CrCL rupture in both knees relatively early in life. Other factors such as obesity, lack of fitness, individual conformation, abnormal gait, increased tibial plateau angle (backwards slope at the top of the tibia), hormonal imbalance, and certain inflammatory conditions of the joint may also play a role.

How can I tell if my dog has cruciate ligament disease?

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is the most common cause of pelvic limb (hindlimb) lameness in the dog, and limping is the most common sign of CrCL injury. This may appear suddenly during or after exercise in some dogs, or it may be progressive and intermittent in others. Some dogs are simultaneously affected in both knees, and these dogs often find it difficult to rise from lying down and have a very “pottery” gait. In severe cases, dogs cannot get up at all and can be erroneously suspected of having a neurological problem. Some dogs will also show atrophy (wasting) of the quadriceps muscle (thigh muscle), instability of the knee, formation of periarticular fibrosis (so-called medial “buttress”), which is thickening of the tissues around the joint, and joint effusion (swelling). It is likely that various interrelated factors contribute to the rupture or degeneration of the cranial cruciate ligament in dogs.

What is happening inside an affected joint?

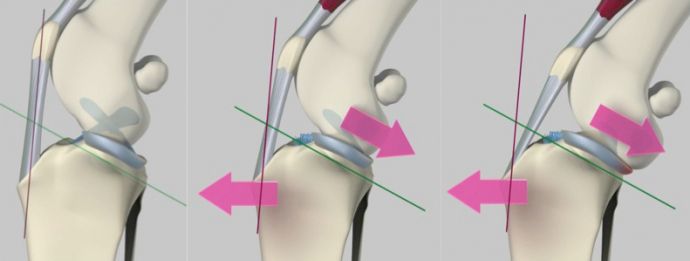

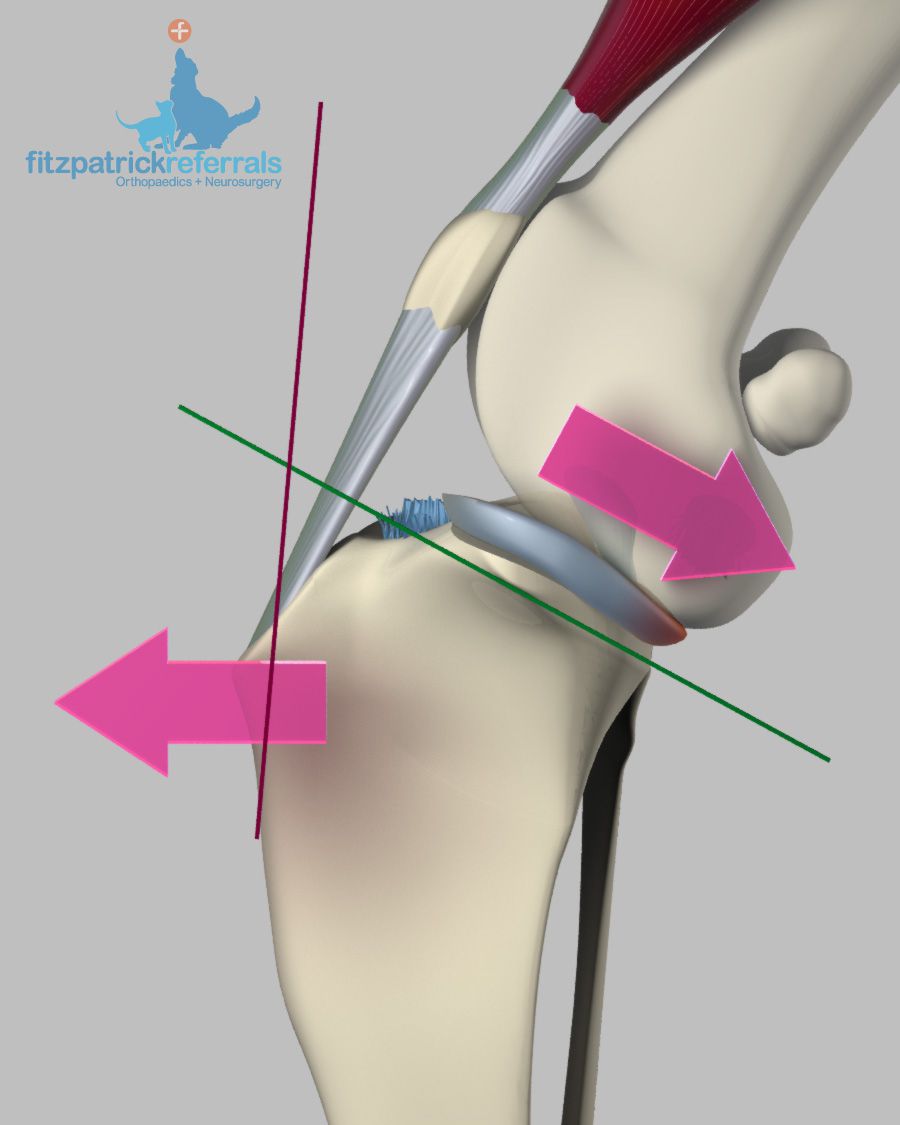

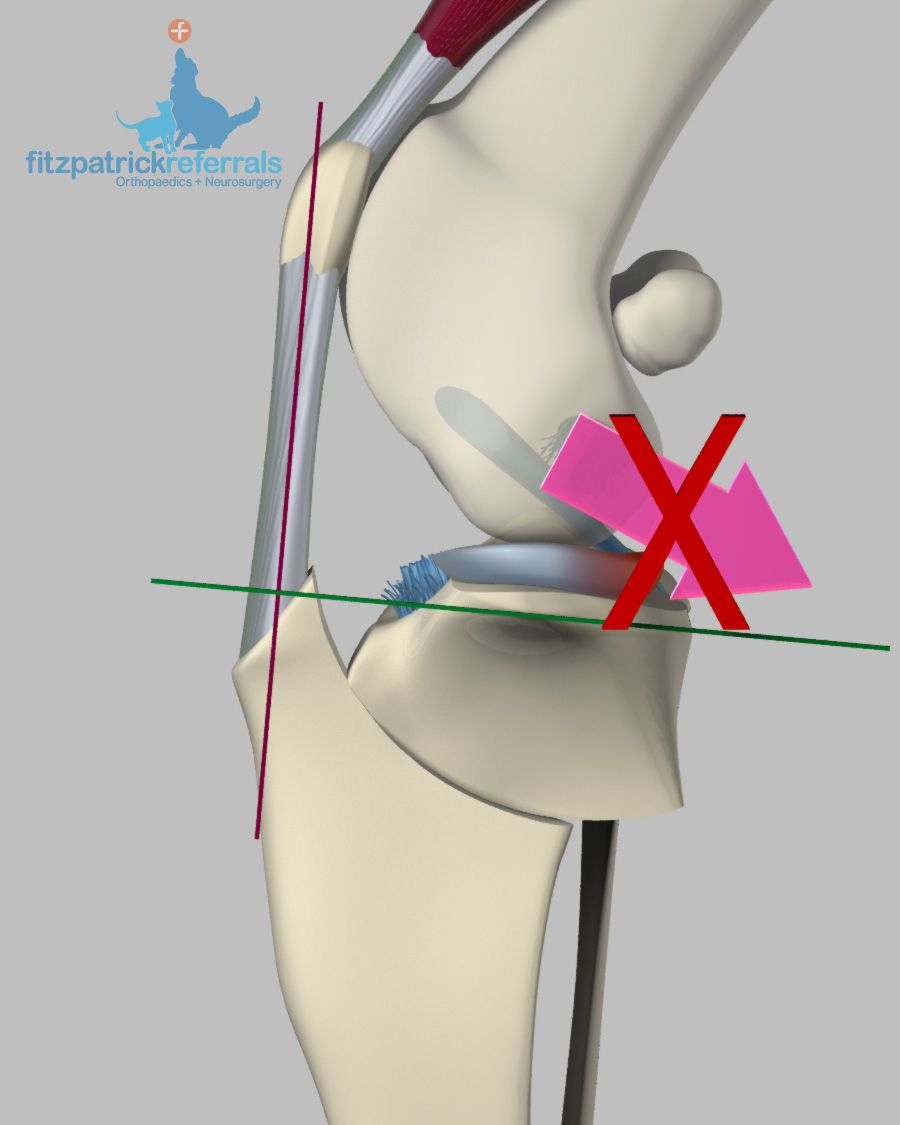

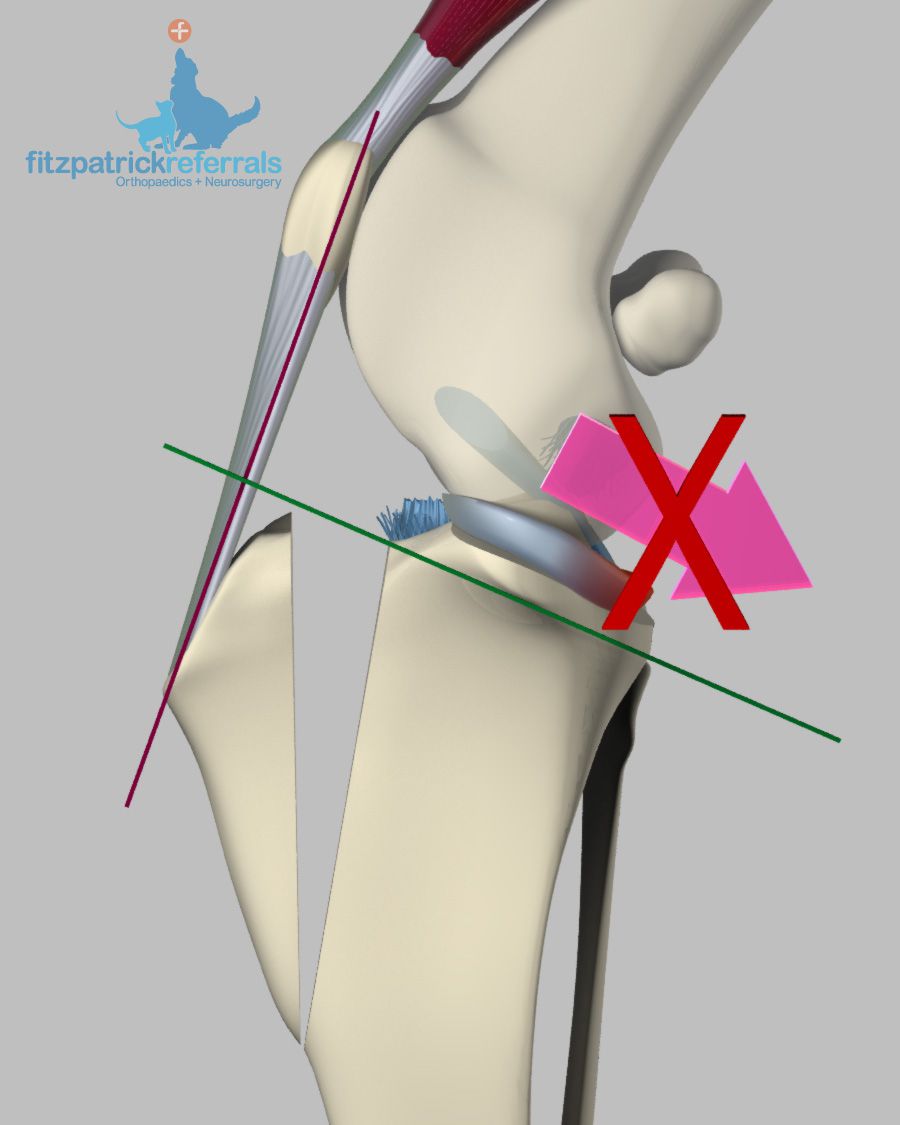

Fraying of the ligament triggers a cascade of events inside the joint, which result in knee pain and lameness. At the earliest stage of CrCl degeneration, osteoarthritis is already present in the joint. It is important to accept this, because many people ask “when will my dog get osteoarthritis?” when in fact the dog has it already. At a critical point of fraying, the CrCL loses its normal mechanical function and painful lameness is accompanied by a mechanical lameness. One of the factors influencing the mechanical lameness is the shape of the top of the tibia that has a pronounced backwards slope in dogs (Image 2). The consequence of this slope in dogs with a ruptured CrCL is that the femur will roll down the slope every time the dog bears weight on the leg. In dogs without impairment of the CrCL, this slope will only become a problem if it is very steep and can, indeed, predispose to CrCL problems.

In some dogs, knee instability can result in damage to other important structures within the joint, the menisci. These are the pair of buffer cartilages, similar to the ones in people, that are sitting between the tibia and the femur. When the femur is slipping down the slope of the tibia, it can crush and tear these cartilages, particularly the one on the medial aspect (inner side) of the joint. These tears may lead to a continued lameness, and additional surgical treatments may be recommended.

How is cranial cruciate ligament injury diagnosed?

Diagnosis in dogs with complete rupture of the CrCL is usually based on examination by an experienced orthopaedic surgeon. The joint laxity can be demonstrated by specific manipulations of the knee, called the “cranial drawer” or the “tibial compression test”. Knee instability will be present in many, but not in all dogs. In dogs with partial tears, or early degeneration of the ligament, other tests may be necessary, including radiography (x-rays), CT, or MRI scans.

To be of maximum benefit, radiographs must be of optimal quality. In most dogs, exploratory surgery where the joint is accessed surgically either with arthrotomy (a small approach through the soft tissue) or arthroscopy (keyhole surgery) is used to confirm the diagnosis and to investigate for possible tears of the menisci or other problems. In some cases, a joint fluid sample may need to be analysed to rule out an infection within the joint.

How is cruciate ligament injury treated?

Non-surgical management

Non-surgical management is seldom recommended, except where the risks of a general anaesthetic or surgery are considered excessive (e.g. patients with severe heart disease, uncontrolled hormonal disorders or immune conditions, etc.). The cornerstones of non-surgical treatment are bodyweight management, physiotherapy, exercise modification and medication (anti-inflammatory painkillers). These same tools are also important in the short-term after surgical treatment; however, the primary surgical aim is to reduce or abolish the requirement for long-term exercise restriction and medication. Dogs greater than 15kg have a very poor chance of becoming clinically normal with non-surgical treatment. In dogs weighing less than 15kg and cats some improvement can be observed, but it takes several months and they will rarely go back to normal exercise.

At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we are able to provide you with a rehabilitation plan for cranial cruciate ligament disease for your dog. This is coordinated through our rehabilitation service, which consists of a team of very experienced chartered physiotherapists and hydrotherapists. Your orthopaedic clinician will coordinate an appointment with one of our physiotherapists. A thorough examination will be performed, and an individual rehabilitation plan will be designed for your dog, including a home exercise plan for you to follow. Most physiotherapy appointments are attended as an out-patient; your physiotherapist will evaluate your dog’s progress at every appointment and amend your home exercise plan as necessary.

Surgical management

Surgical treatments are categorised into techniques that aim to replace the deficient ligament and those that render the ligament redundant and will give your dog a stable knee by changing the biomechanical forces in the stifle joint after cutting and re-aligning the tibia.

Ligament replacement techniques

Various surgical techniques that mimic the procedures used for ligament replacement in humans have been performed since the 1950s.

In dogs, techniques that transfer local tissues have the poorest chance of returning limb function to nearly normal. This is because the replacement tissues are not as robust as the original ligament and they are positioned in the same unfavourable biomechanical environment that caused the original ligament to fail in the first instance. These replacement tissues also weaken initially due to lack of blood supply before being able to establish new blood supply during the healing phase.

Prosthetic ligaments have also been used for many years. These are simple techniques that can return many animals to near normal function. The most important disadvantages of these techniques are that recovery during the early stage is unpredictable and that they have mechanical limitations in heavy and athletic dogs. Some dogs become initially more lame before improvement occurs., others take many weeks to improve and a proportion will have ongoing knee instability and pain. Variations of this technique are most commonly recommended for dogs with traumatic cruciate ligament injuries or when several ligaments of the knee are damaged, so-called “multiligamentous injuries”.

While the described techniques “replace” the cruciate ligament “inside” the joint, other techniques try to mimick the stabilising function of the ligament with extracapsular (outside of the joint) techniques. For decades, sutures of nylon with various knotting and crimping systems have been placed between the fabella (a small bone at the back of the knee) and the top of the tibia via a tunnel. This so-called fabello-tibial suture or lateral fabellotibial suture have had variable reported success rates dependent on material and technique. The difficulty with this technique is that it tries to replicate the exact origin of the “natural” cruciate ligament on the femur and insertion on the tibia as reference points (isometric points). In reality, this is impossible and so the principle has been referred to as using “quasi-isometric” points. High success rates have been reported for the Arthrex “TightRope™” technique which uses a synthetic material called Fibretape™ or Fibrewire™ which are placed through bone tunnels in the femur and the tibia and fixed with bone anchors. In patients where we adopt replacement of the ligament, this is the technique we employ.

Treatments that render the cranial cruciate ligament redundant

These surgeries alter the geometry of the knee joint in such a way that the cruciate ligament is no longer necessary to maintain knee stability. There are several variations in technique, which all involve cutting the top of the tibia and subsequently fixing it in a new position. At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we offer the tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO) technique.

Tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO)

This surgery involves the creation of a curved cut in the top of the tibia and rotation of the tibia plateau (upper part of the tibia) segment until the previous slope of the tibia is no longer present and the plateau is flat; the femur cannot slide back anymore on the tibia. The rotated segment bone is subsequently fixed in this new position using a plate and screws.

Video of TPLO thrust from Fitzpatrick Referrals on Vimeo: This video illustrates what happens when a TPLO is performed.

Fitz Rotation Osteotomy Guided (FROG) plate

If a patient experiences a complication after TPLO surgery, for example, when the tibia osteotomy (cutting) technique has failed and the original cut bone segment is unstable, here at Fitzpatrick Referrals, we have the possibility to perform revision surgery. Based on preoperative CT images of the individual patient, we can design the patient-specific Fitz Rotation Osteotomy Guided (FROG) plate. This FROG plate has more screws in the upper part of the plate, which allows us to safely stabilise the original cut bone segment that has become unstable.

Tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA)

This surgery follows the same principle as TPLO, with a cut being created in the tibia to allow a change in geometry that renders the cruciate ligament redundant. The mathematical principles behind TTA are more complex than those behind TPLO; the basic principle is that an altered direction of pull from the quadriceps muscle group (large thigh muscles) produces a force across the knee joint that neutralises the tendency for the femur to roll down the slope of the tibia. In effect, both TTA and TPLO aim to render the tibial plateau perpendicular to the straight patellar tendon and in doing so, neutralise the forces to prevent the sliding of the femur down the slope of the tibia.

Video of TTA thrust from Fitzpatrick Referrals on Vimeo: This video illustrates what happens when a TTA is performed.

What are the advantages of surgeries like TPLO and TTA that involve cutting of bone?

Because bone healing is more efficient than ligament healing, these bone-cutting techniques are more successful than surgeries designed to replace the damaged ligament. The major practical benefit is a very reliable return of limb use, with all dogs expected to start weight bearing on the operated limb within 1-3 days after surgery. The mechanical advantages of TPLO and TTA coupled with the rapid return to function is especially important for heavy dogs, athletic dogs, dogs presenting with mild lameness (where ligament replacement could make them much lamer initially), and in animals with cranial cruciate ligament injuries affecting both stifle joints. In some dogs with CrCL injuries in both knees, TPLO can be performed on both knees during one anaesthetic. Fitzpatrick Referrals has published a large case series documenting efficacy in this regard. This is not possible when using ligament replacement techniques.

At Fitzpatrick Referrals, our preferred technique is TPLO, which we carry out routinely.

Are keyhole surgical techniques employed for the management of cruciate ligament injuries?

We have developed a refined technique for arthroscopic (keyhole) examination of the knee joint. This gives us a magnified panoramic view of the inside of the joint. In all dogs we inspect the joint to assess whether secondary injuries to the menisci (buffer cartilages), have occurred – this is performed either arthroscopically or via open surgery. If a meniscal injury is diagnosed, this is treated surgically by partial meniscectomy or hemimeniscectomy (meniscal trimming) by keeping the peripheral (outside) meniscal rim wherever possible to preserve as much functional meniscus as possible. Meniscal repair by suturing the damaged meniscus may also be appropriate in selected cases.

What are the success rates of TPLO and TTA?

As a general rule, over 90% of dogs return to normal activity after TPLO or TTA, meaning that owners are unable to detect lameness at home. We expect dogs to return to unrestricted exercise without any requirement for ongoing medications after TPLO and TTA with performance dogs like sniffer and military patrol dogs being expected to return to work. The success rates for TPLO and TTA are very similar. At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we routinely use gait analysis by means of a pressure mat on which the dog walks, to give us objective parameters on well the dog is bearing weight on the legs, both before and after surgery.

What are the potential problems or complications after cruciate ligament repair surgery?

Fortunately, complication rates are low when experienced surgeons perform cranial cruciate ligament repair surgery. Complications can include haemorrhage (bleeding); fractures of the tibia, tibial tuberosity or fibula; osteomyelitis (bone infection); delayed bone healing, no bone healing at all, healing of the bone resulting in the wrong alignment of the tibia; injury of the patellar tendon (straight kneecap ligament) or screws that are placed in the joint. The rates of these complications are very low in the hands of experienced surgeons.

The two most common complications are infection and mechanical complications. Infection is treated using antibiotics. In some cases, surgical lavage is necessary and, in the worst cases where bacteria adhere to the implants, the implants must be removed after the bone has healed. In the vast majority of dogs, the implants remain in place for life and cause no problems at all. Mechanical complications usually occur in dogs that exercise too much before the bone has healed – which takes about 6 weeks. Many mechanical complications are managed with rest alone, although some problems require surgical revision. A rare complication is late injury to the menisci (buffer cartilages) and can require treatment, which is usually performed using keyhole surgery. Other rare complications including sprains and strains around the knee joint can generally be managed using physiotherapy alone. Fitzpatrick Referrals has published a large case series with dogs that had TPLO surgery, which showed a low complication rate and where only few dogs required subsequent intervention.

Rehabilitation

We recommend a follow-up appointment with an ACPAT (Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Animal Therapy)-registered physiotherapist in 7-10 days or as advised by your surgeon in your discharge instructions. Clients are welcome to return to Fitzpatrick Referrals as outpatients at our rehabilitation centre. Alternatively, details of a local ACPAT-registered physiotherapist can be found on www.ACPAT.org.

Read our rehabilitation of cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) disease guide for further information.

Patient stories

PATIENT STORY

Teddy’s bilateral TPLO for cruciate ligament disease

Meet four-year-old Teddy, a gorgeous West Highland White Terrier cross. Rescued when he was three months old, Teddy has been living a happy…

PATIENT STORY

Pepper’s bilateral single session TPLO for cruciate ligament disease

Pepper is a sweet-natured, five-year-old Cocker Spaniel from London. She was referred to Fitzpatrick Referrals Orthopaedics and Neurology by her vet at Molly…

13 minute read

In this article