What is intervertebral disc disease (IVDD)?

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is the most common spinal disease in dogs and is also seen occasionally in cats. The most common spinal surgery performed in the dog is for intervertebral disc disease.

Intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous cushions between the vertebrae (except the first two cervical vertebrae) that allow movement, are supportive and act as shock absorbers. They consist of a fibrous outer rim, the annulus fibrosis, and a jelly like centre, the nucleus pulposus. Intervertebral disc degeneration results in diminished shock-absorbing capacity, and can ultimately lead to disc herniation and spinal cord compression.

What causes intervertebral disc disease and are there certain breeds at risk?

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is an age-related, degenerative condition. However certain, ‘at-risk’ dogs (chondrodystrophic breeds and crosses) can suffer disc problems from when they are young adult dogs. Disc degeneration is thought to occur because of loss of the disc to “hold water” becoming dehydrated. Chondrodystrophic dogs, which characteristically have disproportionably short and curved limbs, for example, the Basset Hound, Dachshund, Lucas Terriers, Sealyhams and Shih Tzus. Thus chondrodystrophoid dogs suffer early degenerative changes in the disc making them likely to herniate. When intervertebral discs of chondrodystrophic dogs degenerate, they can calcify making the discs visible on radiographs.

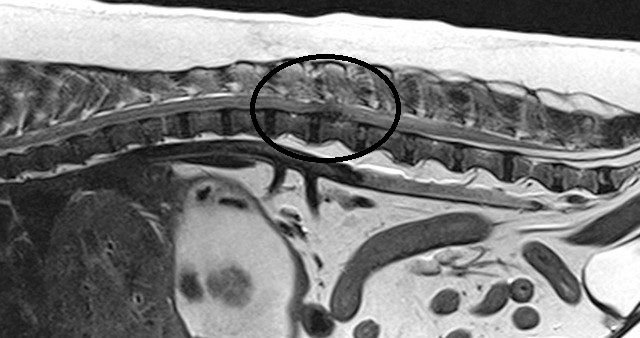

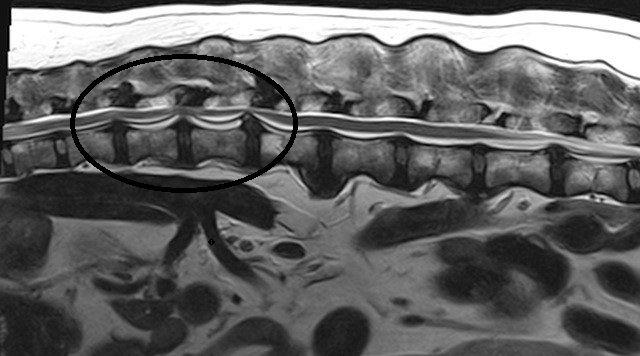

Disc degeneration results in diminished shock-absorbing capacity, and can ultimately lead to disc herniation and spinal cord compression. The types of disc herniation are often described as Hansen type I (nucleus pulposus degeneration and extrusion), and Hansen type II (annulus fibrosis degeneration and protrusion).

Hansen type I disc disease

Dogs with Hansen type-I disc disease is most common in small breed dogs aged 2 years old and above), although larger breeds can be affected. The onset of clinical signs is generally acute i.e. sudden onset. The degree of clinical signs is variable but does influence prognosis, as does the duration of clinical signs. Hansen type-I intervertebral disc disease is most easily described as an ‘extrusion’ or ‘herniation’ of the inner contents of the intervertebral disc. The intervertebral disc structure can be compared to a jam doughnut. The normal disc is compressible and squidgy – they allow the vertebral column to flex, extend and twist. In the diseased disc, the jam (nucleus pulposus) becomes hard and is no longer compressible. Consequently, normal movements (especially twisting) put intolerable strain on the disc and eventually the “doughnut” tears and the “jam” explodes or oozes out. Unfortunately, this is usually in an upwards direction and impacts and compresses the spinal cord above. The velocity of the impact affects the severity of the injury as does the volume of disc extrusion. Clinical signs range from pain to paralysis. Hansen type-I disc disease is a painful disease and in severe cases, an emergency situation and your dog should see a vet promptly so a comprehensive examination can be performed.

Hansen type II disc disease

Dogs with Hansen type-II disc disease are more similar to human disc disease and occur in non-chondrodsytrophic dogs and cats (ie animals without disproportionately short limbs). Instead of an extrusion of the centre of the disc (jam bursting out of the doughnut) there is a bulging and protrusion of the annulus, the outer part of the disc (bulging doughnut). Occasionally the annulus tears and the torn fragment is extruded into the spinal canal compressing the spinal cord. Sometimes acute tearing is associated with bleeding and the blood contributes to the compression. Clinical signs are similar to dogs with Hansen type I disease. Most dogs present acutely but occasionally signs develop insidiously and progressively. In these dogs you may notice reluctance to exercise, rise, jump climb stairs or they may look stiff or have a hunched back. Medium to large breed dogs and cats age 5-12 years tend to be the most represented.

Hansen type III disc disease

Hansen type-III disc disease is also known as ‘acute non-compressive’ or ‘high-velocity low volume’ disc disease. In this case, there is a sudden onset of disease typically with heavy exercise or trauma, causing a normal nucleus to explode from a sudden tear in the annulus. The injury to the spinal cord does not result in ongoing spinal cord compression and with rehabilitation and physiotherapy patients tend to recover without surgical intervention.

The consequence of disc herniation is pain and in more severe cases there may be difficulty walking – ranging from poor control of the hind limbs, a ‘drunken sailor’ walk to complete paralysis. Very severe cases may develop myelomalacia (softening and dying of the spinal cord) and as it ascends the spinal cord, is usually fatal since it affects the nerves involved in breathing resulting in respiratory arrest.

How can I tell if my dog has intervertebral disc disease (IVDD)?

The most common sign associated with intervertebral disc disease is pain localised to the back or neck. As nerve fibres flow from the brain to the muscle along the spinal cord, the clinical signs will refer to spinal cord dysfunction ‘down-stream’ of the injury, hence disc disease in the lower back can cause hind limb weakness, paralysis or urinary incontinence. Disc disease in the neck can cause weakness on all four limbs.

Apart from yelping, common signs of spinal pain are abnormal posture (e.g. hunched back with head down), shivering, panting, unwillingness to move, difficulty jumping, and going up and down stairs. In more severe cases, there may be difficulty walking, ranging from poor control of the hind limbs – either weakness or a ‘drunken sailor’ walk – to complete paralysis. Most severe cases have a paralysed bladder and may be unable to urinate and/or dribble urine. The most severe cases are paralysed, have lost bladder function and have lost the ability to feel painful sensations.

How is intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) diagnosed?

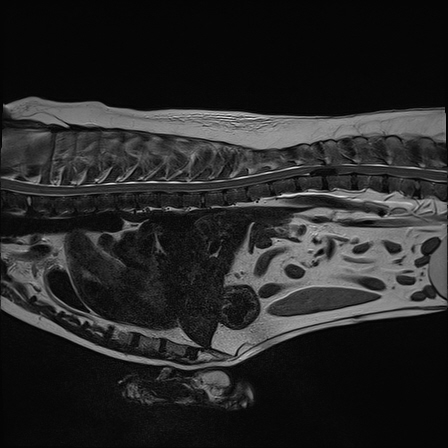

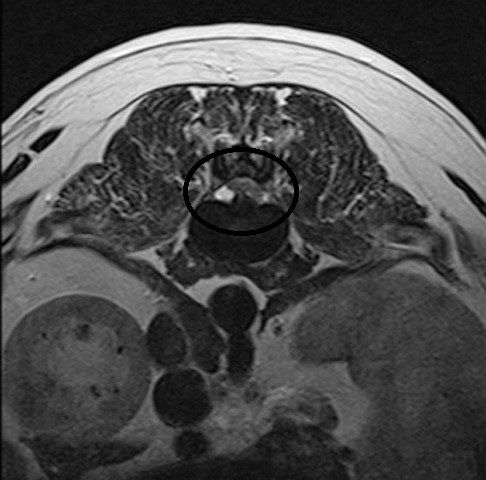

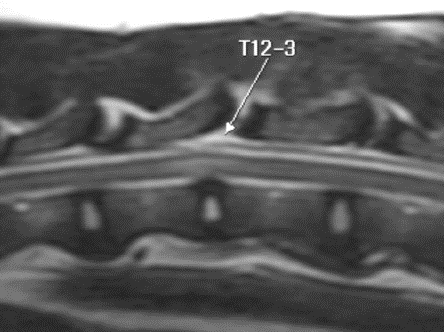

Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) may be strongly suspected on the basis of clinical signs especially in predisposed breeds, however, diagnostic imaging is required to confirm the diagnosis. Spinal radiographs may reveal characteristic changes of disc disease e.g. calcified disc material within the vertebral canal or narrowing of the IVD space or the foramen, however, radiographs rarely provide the accurate conformation and localisation required for surgical management.

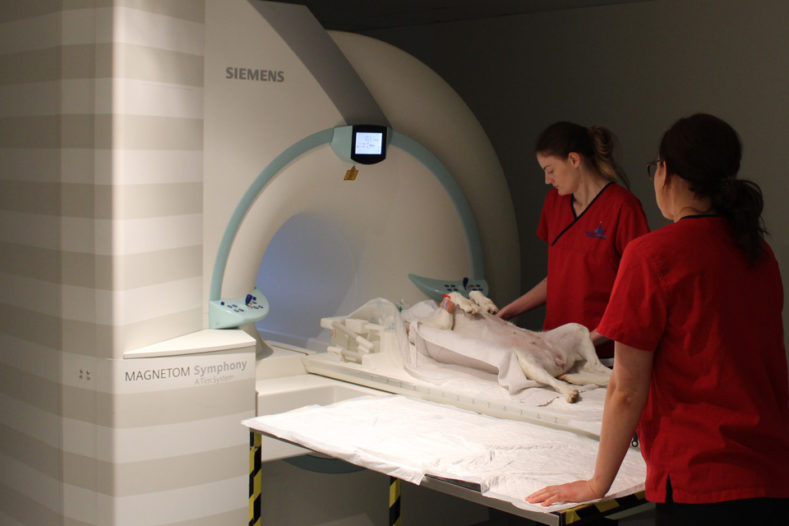

Advanced imaging is required to allow a definitive diagnosis. At Fitzpatrick Referrals, we have MRI and CT scanners within the hospital, which allow rapid diagnosis and surgical planning. This provides more information than radiographs for diagnosis and surgical planning. Patients must lie completely still for their scan and this is only possible with the use of general anaesthesia. Your dog will have dedicated one-to-one care during their MRI or CT scan by one of our nurses from the prep nursing team who are all trained and experienced in anaesthesia and sedation.

Is conservative management an option and what does it involve?

Conservative management is indicated for patients with pain only or for those with mild deficits although there may be success with more severe cases. Dogs which have lost pain sensation are a surgical emergency and are extremely unlikely to respond to conservative management. Disadvantages of conservative management include a higher rate of recurrence of clinical signs and a higher chance of deterioration or persistent neurological deficits. In addition, diagnostic tests may not be performed so the animal may be receiving inappropriate treatment.

Conservative management has the advantage that it is comparatively inexpensive and avoids surgery. The most important aspect is restriction of movement i.e. cage or crate confinement. This limits further IVD extrusion and exacerbation of the injury. The animal’s natural healing process can then repair the damage to the spinal cord. Should your dog remain in the hospital for conservative management, all of their daily needs including pain management, feeding and general TLC will be provided by our patient care team. They will also ensure their home comforts are at hand. If you are providing conservative management for your dog at home, your neurology clinician will keep in close contact with you to monitor your dog’s progress and allow the opportunity to identify any signs of deterioration. They will also ensure your dog receives adequate pain relief if required.

Will my dog need to have surgery?

Many cases will do well when managed conservatively however in cases with paralysis, the prognosis is better with surgery i.e. the dog or cat is more likely to regain walking function and be pain-free, is more likely to improve quickly and less likely to have recurrences. Cases where pain sensation is absent (i.e. when the toe is pinched hard but the dog or cat is unaware of discomfort) are a surgical emergency and have a poor prognosis for improvement.

What does the surgery involve?

There are two categories of disc surgery.

Fenestration surgery

The easiest surgery and one that does not require specialised equipment is fenestration. In this procedure, the nuclei pulposus of thoracic vertebrae T11/T12 to lumbar vertebrae L3/L4 (in the case of a thoracolumbar disc extrusion) or all the cervical intervertebral spaces (in the instance of cervical disc disease), are removed through a small window created in the annulus fibrosis. This is a prophylactic procedure limiting further disc extrusions. The disc material within the vertebral canal is not removed and if the dog has severe spinal cord compression then the neurological recovery will be prolonged and/or there will be residual neurological deficits. Fenestrations may or may not be done in combination with a decompressive surgical technique.

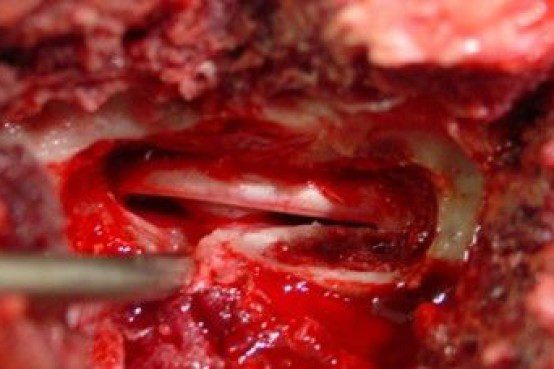

Decompressive surgery

The second type of surgery is decompressive i.e. the extruded disc material is removed from the vertebral canal. This surgery is more technically difficult and requires specialised equipment and training. The type of decompressive surgery performed depends on the site of the problem. In the neck, a ventral (underside) approach is favoured (a ‘ventral slot’) and a window is drilled through the vertebral bodies. For the thoracolumbar spine, the most common procedure is a hemilaminectomy, where entry into the vertebral canal is made from the side, directly above the disc space and the vertebral foramen. For lumbosacral problems, a dorsal laminectomy is used where the ‘roof’ is taken off the vertebral canal allowing direct visualisation of the cauda equina and the lumbosacral disc.

How long does spinal surgery for disc disease take?

This type of surgery can take between one and three hours, depending on the complexity of the procedure.

What happens to my dog after surgery?

Immediately after surgery, your dog will be given the opportunity to recover from the anaesthetic peacefully. Postoperative analgesia (painkillers) and supportive therapy will be provided in our designated recovery ward where your dog will be monitored and nursed by a dedicated team of nurses and vets. Ultimately rest and recuperation from the anaesthetic are the most important factors until the morning when your dog will be transferred to the surgical ward to continue nursing care by our ward nurse team and ward auxiliary team.

Following assessment from their surgeon, your dog will be assessed by our specialist team of chartered physiotherapists and they will design and implement a physiotherapy and rehabilitation programme for rehabilitation of intervertebral disc disease specific to your pet. Physiotherapy plays a vital part in the treatment of animals with spinal cord disease. Inactivity and recumbency result in decreased joint movement, stiffness and muscle weakness and contracture.

When can my dog go home after spinal surgery?

The length of stay in hospital following spinal surgery varies from patient to patient depending on their comfort levels, functional movement and urinating ability. Generally, all dogs will stay in the hospital until they can urinate independently. Upon discharge, you will have an appointment with one of our chartered physiotherapists and your dog whereby you will be taught how to perform the necessary physiotherapy techniques and exercises to ensure your dog continues to make progress at home. During this appointment, any outpatient physiotherapy and/or hydrotherapy appointments will also be scheduled through our very own rehabilitation service at Fitzpatrick Referrals.

How long before my paralysed dog will walk again?

This is very variable in each and every dog. Typically recovery occurs over a period of several weeks. Some cases improve more quickly and, sadly, in some cases there is no improvement.

Are there any solutions if my dog does not regain a functional walking ability?

Some dogs continue to enjoy life in mobility carts. However, a limiting factor can be bladder control. Many patients paraplegic after spinal injury have to have their bladder emptied manually (expressed) or they have an automatic bladder (i.e. involuntarily empties when full like a baby). Bladder expression is not technically difficult and can be taught, it just takes practice to master the technique. Our team of nurses will be able to teach you how to do this. Teaching usually begins while your dog is still in the hospital and we will organise teaching sessions when you visit your dog in preparation for going home. If you decide to purchase a mobility cart for your dog, we will make sure all the measurements are taken correctly according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. We will also make sure the cart fits your dog correctly when it arrives and adjust as necessary to make sure the first steps are taken with confidence.

Demonstration of manual bladder expression in a dachshund unable to urinate and empty their bladder on their own.

Will the problem reoccur?

If the spinal surgery has been successful then it is unusual for there to be a problem with the same disc. However, there may be a problem with other remaining degenerate discs. If possible other “at risk” IVD are fenestrated at the original surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Patient story

PATIENT STORY

Ellie’s intervertebral disc extrusion (IVDE)

The smallest gestures by our animal friends, like the wag of their tail, may seem insignificant, but for little Dachshund Ellie here, it…

PATIENT STORY

Rocky’s intervertebral disc disease (IVDD)

11-year-old Rocky, is a friendly Yellow Labrador from Surrey, under the care of Neurology Resident Carina Rotter. Rocky’s sudden inability to walk and…

13 minute read

In this article