What is SRMA?

Steroid responsive meningitis-arteritis (SRMA) in dogs is an ‘immune mediated’ or ‘auto-immune’ condition where inflammation occurs in the blood vessels in the lining of the nervous system (the meninges). Infections of the nervous system are uncommon in dogs in the UK due to vaccinations.

How can I tell if my dog has SRMA?

The main clinical signs of SRMA are spinal pain and an elevated temperature – this pain is severe in the neck but can also be present to a lesser extent in the lower back. The pain is most severe when trying to touch the chin to the chest. Other neurological abnormalities are not expected with this condition. Most dogs will be inappetent and reluctant to exercise.

Inflammation can affect other parts of the body – typically the joints. Swollen joints can cause a stiff and stilted way of walking. Rarely animals with SRMA can have inflammation of other inner body surfaces, like the covering of the heart (potentially causing abnormal heart rhythm), lungs and abdominal contents (causing the development of some fluid).

What is the cause of SRMA?

We are not normally able to establish why an animal develops an immune-mediated disease. We recognise SRMA most commonly in young (<2 years of age) dogs of certain breeds including Beagles, Boxers, Bernese mountain dogs and Weimeraners but dogs of any breed can be affected. A complex interaction of genetics and the animal’s environment probably contribute to developing the condition.

It seems the juvenile immune system produces inflammation and antibodies against a normal body protein – in SRMA this is a protein expressed by the walls of blood vessels in the meninges.

There is no infection with this condition and the condition is not contagious.

How is SRMA diagnosed?

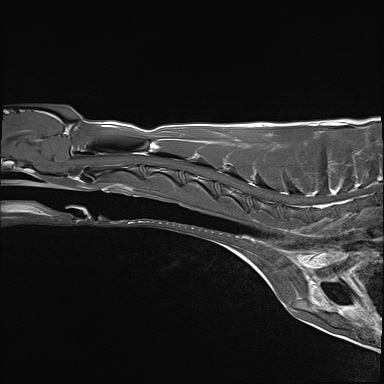

A diagnosis is normally made on the basis of first excluding other causes of spinal pain (like bone or soft tissue infections, immune-mediated joint disease, infections) by obtaining a blood sample and performing radiographs. Then, cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) analysis is performed by obtaining a sample of CSF from the neck or lower spine (or both) in a sterile manner under general anaesthesia. Your pet will have dedicated one-to-one care during their CSF tap by one of our nurses from the prep nursing team who are trained and experienced in anaesthesia and sedation. The demonstration of inflammation and the presence of a specific type of inflammatory cell facilitate a presumptive diagnosis. Although infection is very unlikely, we will normally run a panel of various blood and urine tests to exclude this possibility.

How is SRMA treated?

The mainstay of treating SRMA is suppression of the immune system with drugs, particularly high doses of corticosteroids like prednisolone. The administration of high doses of steroids by injection or orally very often results in significant and rapid improvement or resolution of the clinical signs. The dose is then reduced slowly over the course of several months until the stimulus for the immune system has gone.

Unfortunately, side effects are often seen with steroid use. Common dose-dependent side effects of steroids include increased thirst and hunger (consequently urination and weight gain), lethargy, panting, and increased risk of infections (respiratory, urinary etc).

Occasionally additional medications are required, such as cyclosporine and azathioprine which are given orally, either to aid suppression of the immune system or to allow us to reduce the steroid dose without fear of relapse. These medications can be given to your pet at home.

Your veterinary neurologist or primary care vet will discuss with you what side effects may be expected with medication.

What is the prognosis of SRMA?

The prognosis for SRMA is generally very good, with most patients improving after 2-3 days of treatment and entering clinical remission within 2 weeks.

Treatment with steroids is normally required for 5-7 months, after which treatment can be stopped and a normal length and quality of life can be expected.

Relapses of SRMA are possible either during the course of treatment or after treatment has been stopped. Roughly 20% of patients with SRMA will relapse. If they do, the clinical signs will be similar or identical to the original syndrome. Normally with a ‘step-back’ in the treatment regime a relapse can be successfully treated.

Occasional visits to your neurology clinician or primary care vet may be required during the course of treatment. They may also suggest blood tests every few months to assess the function of organs that may be affected by treatment. How often this is required will be dependent on your pet’s response to treatment.