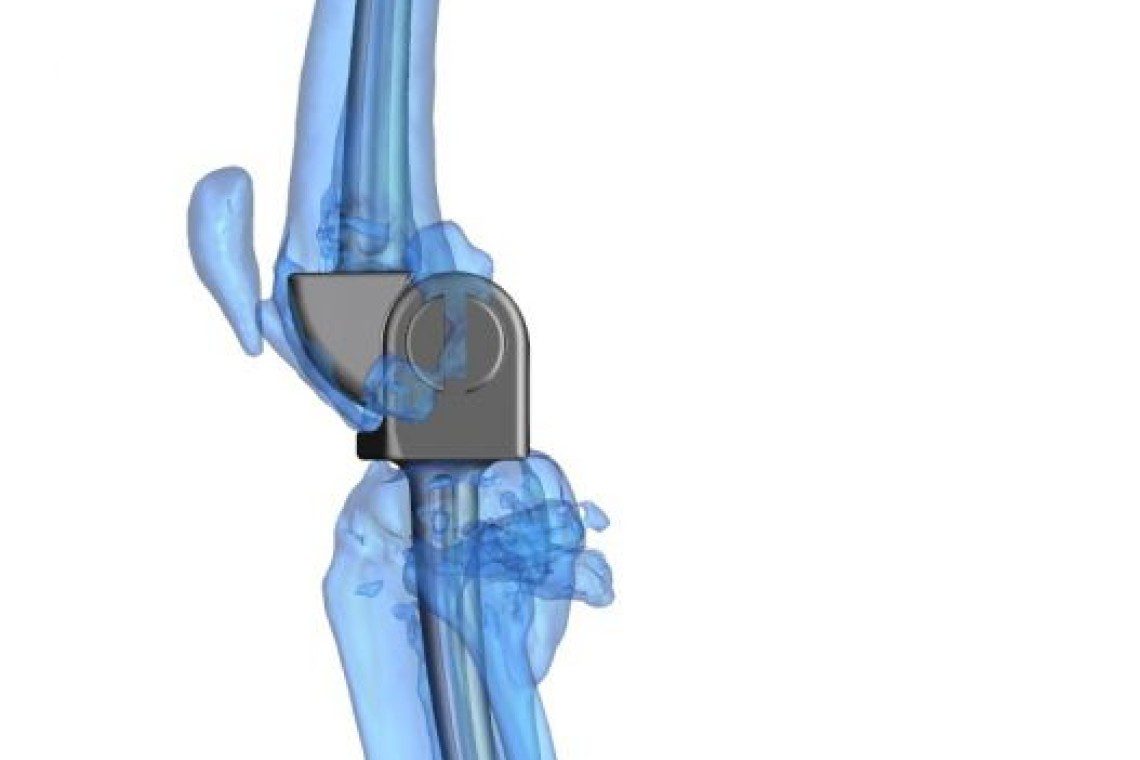

Total knee replacement is used to treat end-stage disease of the knee joint with the hope of restoring pain-free function.

What is total knee replacement?

Total knee replacement involves cutting out the entire diseased knee joint and replacing this with a prosthetic joint just like in humans. Fitzpatrick Referrals is proud to be the only practice in the UK that can offer total knee replacement for cats.

How can I tell if my cat would benefit from a total knee replacement?

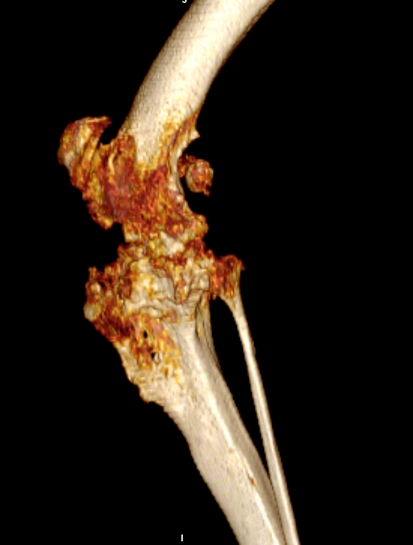

Total joint replacement of any joint carries the risks of possible complications. Total knee replacement is reserved for cats that have painful conditions of the knee joint that have proved unresponsive to conventional surgical techniques or conservative management using pain relief and rehabilitation. The most common cause of knee joint pain is osteoarthritis secondary to cruciate disease, trauma or malformation of the knee joint. We can also use total knee replacement in cats to treat certain types of bone tumours that affect the knee joint and to repair joints that have been disfigured following trauma and have no ligamentous support left. Historically full limb amputation was commonly recommended for such situations but now we are proud to provide an alternative option allowing your cat to have a normal lifestyle.

The primary goal of total knee replacement surgery is to restore pain-free function. In most cases, it is possible to restore joint function to a level similar to that of a healthy knee joint albeit that the postoperative gait may not look entirely normal. Cats that have had successful total knee replacement surgery do not normally require long-term medical management using pain relief medications.

What types of total knee replacement are available?

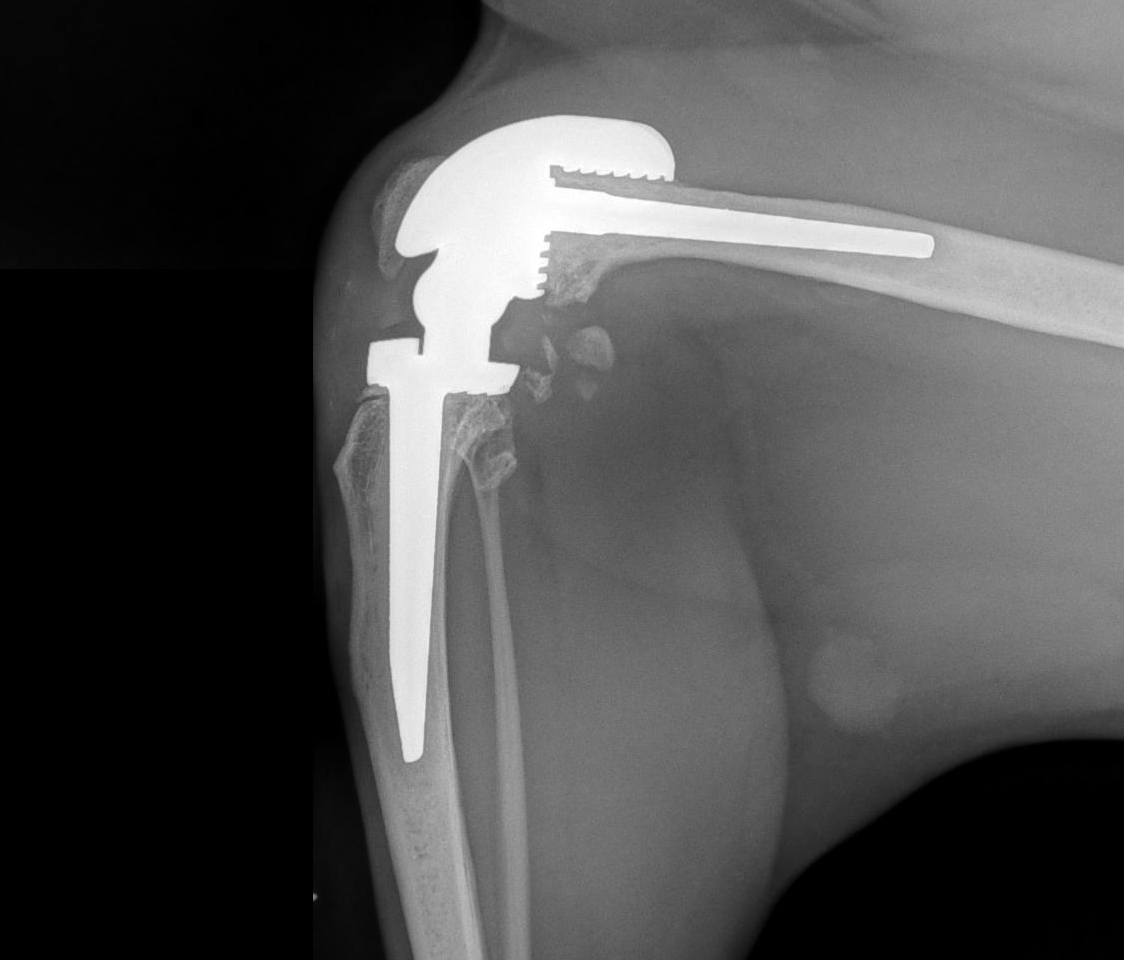

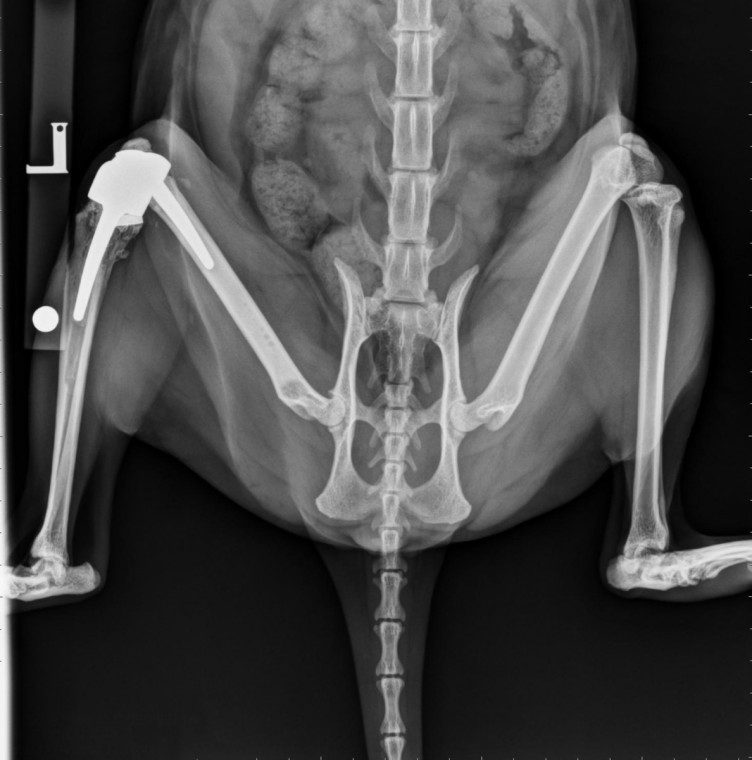

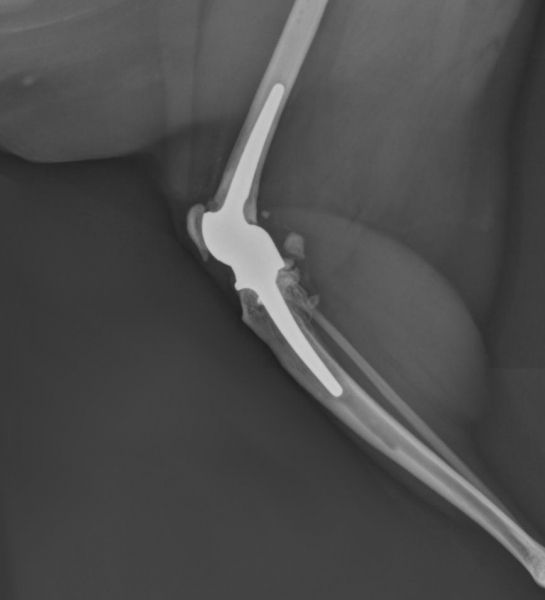

Currently, there is no commercial total knee replacement available for cats and the canine commercial system is too large for use in cats. Fitzpatrick Referrals has pioneered the development of custom-made total knee replacement implants for our feline companions. Detailed CT images of your cat are obtained through our advanced diagnostic imaging service and our medical engineers use this 3-D information to design an implant that exactly fits the dimensions of your cat’s knee joint. Once the design process is complete the implant is manufactured using a process known as laser sintering, which allows intricate metal designs to be created. Once this stage is complete, your cat can be scheduled for surgery.

What does total knee replacement surgery involve?

During surgery, the knee joint is exposed through an incision on the side of the knee. The joint surfaces of both the femur and tibia are removed en-bloc and the implant is cemented into place using orthopaedic cement. The success of the canine commercial surgical system relies on the supporting ligamentous structures of the knee joint, however, the hinged design we have developed means that the supporting ligaments of the knee do not play a role in the success of the surgery.

What are the risks of total knee replacement?

The most significant risks associated with total knee replacement surgery are implant loosening, failure of the supporting ligamentous structures and infection. Infection is a rare but potentially devastating complication of any surgical procedure. The risk of loosening is also rare. Careful postoperative management of the patient helps prevent damage to the implants.

Are there reasons why my cat shouldn’t have total knee replacement surgery?

If your cat’s knee pain is effectively controlled with drugs and rehabilitation, it is unlikely joint replacement surgery would be recommended. Total knee replacement may, however, be offered when your cat’s pain can no longer be managed using conservative means.

Pre-existing infection is a contraindication to total knee replacement surgery. Additional reasons why surgery may not be recommended include lameness associated with arthritis in other joints, neurological disease and previous amputation of a forelimb or opposite hind limb. These conditions do not necessarily preclude total knee replacement but the final decision is made on a case-by-case basis.

What is the typical recovery time after total knee replacement?

Recovery depends on the severity of the preoperative arthritis and can be improved by following a structured postoperative rehabilitation programme that is constructed by our chartered physiotherapists in collaboration with your cat’s clinician. Careful rehabilitation after total knee replacement is the key to success and it is vital that patients who undergo this surgery are managed diligently for the first 7-10 days after surgery to prevent damage to the operated knee.

During your cat’s hospitalisation period, they will be cared for by a dedicated team of ward nurses and patient care auxiliaries who work alongside the clinician, a team of veterinary surgeons and chartered physiotherapists, ensuring all your animal friend’s clinical and emotional needs are met. Our patient care team endeavour to make sure that your cat feels at home in the hospital, so be rest assured they will be cared for by each of our team members as if they were their own, with the love and affection they desire and deserve.

After the initial 10 days, patients are placed on a carefully managed exercise programme that gradually returns them to normal exercise and lifestyle by 12 weeks after surgery. Cats are most frequently managed with cage-based rest in the postoperative period.

What alternatives to total knee replacement are available?

Arthrodesis, or fusion of the knee joint, may be a viable alternative in patients that are not suitable for total knee replacement although function is particularly sub-optimal in comparison to total joint replacement.

What should I do if I think my cat needs a total knee replacement?

If you think your cat needs a total knee replacement, we recommend asking your primary care vet to contact us for further advice. We are more than happy to talk to your vet about what is involved with the surgery and ascertain if total knee replacement could help your cat.

7 minute read

In this article